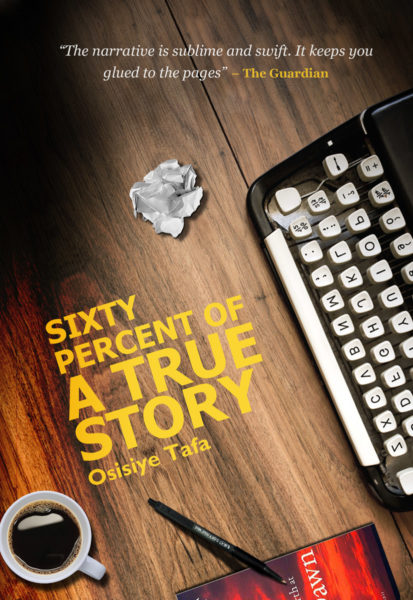

Forget what you have heard in the past and what people will try to tell you about truth being sacrosanct; it is subjective. There’s a version of every truth that is filled with inaccuracies, but who’s to say which is which? This is how I felt when I finished reading Sixty Percent of a True Story by Osisiye Tafa.

Forget what you have heard in the past and what people will try to tell you about truth being sacrosanct; it is subjective. There’s a version of every truth that is filled with inaccuracies, but who’s to say which is which? This is how I felt when I finished reading Sixty Percent of a True Story by Osisiye Tafa.

The author of the book, in his foreword wrote: “For me – and everyone I knew – being a student of UNILAG changed our view on life, the opposite sex and money. “ He went on to state: “This story is my attempt to describe my experience and that of my classmates. Going through my correspondence (SMS, e-mails , tweets and Facebook messages) during that period, I was surprised by the range of emotions I experienced. I had expected a fun time. I experienced awe, pride, depression and finally, boredom.”

Those words pretty much set my expectations for the book. As an alumni of the University of Lagos, I was curious, and next to intrigue, curiousity is always a good place to start a book.

Kicking off with a narration of the author’s impression of the institution as set by a dialogue with his sister, we are presented with the image of innocence and naiveté of a young teenager.

She was telling me about University life.

“So my course rep makes plenty money o! See now, if the lecturer tells us hand-out is two hundred Naira, he will tell us it is two hundred and twenty naira

“Twenty Naira, what is he using that one for?”

“Calculate it, she said, eyes widening at my ignorance. We are 150 in the class. So if he gets twenty naira from 150 people, that is about three K. I’m not even counting the people that will forget their change with him o!”

Hmm, that class rep job is good o.”

“Ah you should see how people fight for it. All those Yoruba boys, they fight just because they want to become Class Rep. If you’re the rep, you will get money and you will be close to the lecturer. Some lecturers will even be telling you to get babes for them. That means you cannot fail”

“So does he know book? Is he intelligent?”

“Eh, she shrugged. He tries.”

The pace of the story quickly shifts from the slow burning background, laying to the intricacies of author’s personal experiences.

He describes the University very colourfully, with light and easy writing and witty dialogue. Living in the hostel, the author tells about the interesting potpourri of characters thrown together by the circumstance of seeking higher education in Nigeria.

Osisiye Tafa describes the UniLag hostel in a way that anyone who did not attend the institution would get a clear picture of it. There are times when he slowly falls for the temptation of overly romanticizing the place:

“Bathrooms in Sodeinde are cubicles. You’re bathing and from the next cubicle, you hear Korede, his voice muffled by the steam and the water, talking to you.”

As someone who went to Unilag and lived in the institution, this scene seemed a few percentages away from reality. I was hard pressed to conjure a scene with steam flowing from a bucket and bowl scenario – which seemed closer to the truth. However, the descriptions filled me with a lot of nostalgia, and it was quite enlightening to see how life in the boys’ hostels differed from ours. Osisiye Tafa’s words painted a visceral picture of every hostel I lived in while at UniLag – the wet, dinghy hallways, and the narrow bunk beds.

I enjoyed the unveiling of the characters in the book– the roommates. I wanted to know more about them; but the author doesn’t stay too long with them. The narrative quickly runs through 4 years of his time in Unilag and the book is only 40% complete.

Osisiye then takes us briefly into his life after Unilag – a quick glimpse into his life as a staffer during Dele Momodu’s political campaign. This sharp detour from the previously laid down narrative is where the book begins to take a dip for me. Like an errant car jolting out of a lane in smooth traffic, I am tossed into the next segment captioned: “These are Important… Somehow [Korede]”

The book descends into a spiel masqueraded as a narration from the point of view of Korede, who is one of the previously introduced roommates.

The transitioning to Korede’s section was staggering because it begins with the narration in the author’s voice – picking up from when he saw Korede on his graduation day and then continues with Korede telling his own story from the 1st person point of view.

The ‘Important…somehow’ section did not work for me. Suddenly Korede is telling us his life story and how much difficulty he had fitting in, what they ate for dinner at their house – definitely a marked shift from the original flow of the story. ‘Korede’ then goes on to pontificate at length at all the things wrong with the way adherrents of alternative lifestyles are treated in Nigeria.

It reminded me very much of the large chunks of blog posts laden in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. The hand of the author was heavy in the voice of the character, and while I imagined Osisiye was trying to pass a social conscience message about the inhumane treatment of homosexuals in Nigeria, the long protracted discourse made for tiresome reading.

The close mirroring of Korede’s experience to the coming out of gay rights activist, Bisi Alimi was effective story telling for anyone who wanted to visualize the fascinating back process that must have gone into Bisi Alimi coming out on Funmi Iyanda’s Breakfast show, New Dawn.

By this time in the book, I had no doubt as to the side of the percentage of truth I had stumbled upon. It didn’t help that the section dragged on for too long.

The next section of the book, captioned [Chris], took us into the author’s life AFTER Unilag. While Korede’s section was Korede’s story, told through Korede’s voice, Chris’ section was the author’s narration of how his life turned out as a result of his interaction with Chris. The absence of consistency in the style of narrative did very little for the overall enjoyment of the book for me.

One thing that did remain constant were the large chunks of texts that didn’t necessarily move the narrative forward. Letters written to a 419 practitioner to his ‘maga’ would have made for interesting reading if we were given an insight into the ‘maga’s responses. Just maybe.

Overall the thing that kept me going in he book were the funny bits, and that’s a huge selling point.

The book was not without its “No sh*t, Sherlock” moments: “The Oriental Hotel, Lagos, is a franchise. This means if you walk into the Hotel in Malaysia or any other country, it’s the same as this.”

It is Osisiye Tafa’s first published work, and for the effort and courage it takes to actually put a manuscript together, it is very good book. Sixty Percent of a True Story is an enjoyable and humorous book which can be easily finished in one sitting. Then when you’re done, you have to try and figure out what parts of the book form the 60% of truth.

***

Sixty Percent of a True Story is available for sale at the following places: Amazon, Konga, Terra Kulture and Patabah Bookstores.

Leave A Comment